D.U.N.

Overview

Our final Fall 2017 studio project, Settled, was a culmination of the research and design artifacts our class compiled during the semester. This time, we were tasked with bringing our individual problem space, which we had crafted throughout the course, back to the original studio focus: “rethink and redesign (the culture of) graphic design in the context of contemporary practices, application, and usage” (Gonzales-Crisp, 2017). Students were asked to apply their findings by developing two hypothetical scenarios, one that proposes a Radicalized shift to the design culture and one in which that shift had become Normalized into everyday culture. The following exercises exemplify these scenarios in iterative stages, initial prototypes, further research and final prototypes.

Process Scenarios

Radicalized

The movement begins with the launch of a series of microsites that call upon contributors to revise and alter the design in real time using editable content objects. Consolidating and improving access to the open-source software model, new participants are now able to manipulate these designed artifacts, creating results that are constantly changing according to user input. Rowan begins with a standard website. Basic, legible and used a thousand times over. It gets the job done, just not in a particularly interesting way. Josephine visits the site and decides to change things around. She prefers a blog-style layout and adjusts the size and placement of content. Lucius is a trouble maker. He comes to the site and disrupts the entire flow, hierarchy and sensemaking of the original site. Rowan and Josephine return to the site and are dumbfounded (fig. 1).

Normalized

Visual media, including album art, promotional adverts and concert projections are turned over to patron contribution in efforts to expand the listener’s role in constructing the visual identity of the music. Now, any patron can edit/alter an artist’s graphics content. Patrons perform their contributions on physical products via smartphone and access the results by viewing the product through an augmented reality lens. Changes are updated in real-time so that each new visual experience is different (fig. 2).

Final Scenarios

It is our responsibility as designers to create solutions that are reflective and representative of the spaces, cultures and communities that we design for. Environmental graphic designer Patricia Cué criticizes traditional design approach, writing that “graphic design's practice is largely based in completely eradicating existing solutions — a ‘before’ and ‘after’ approach that particularly disregards vernacular forms or user-generated solutions (Cué, 2014).” In human-centered design, awareness and accountability for the user and their environment is paramount. Relating design decisions to user context is necessary to creating design solutions that accommodate and enhance the user rather than subject them to something impractical, innappropriate or imposing (Greenhouse, 2012). How might designers continue to take this methodology further, perhaps to radical ends? How (or when and where) might the user be inserted into the design process that hasn’t been fully explored? One possibility is to assign more agency to the user in constructing the identity of a designed work or system. For the designer, this may entail relinquishing order and control to the potential chaos of ongoing participation, to “allow for re-purposing, appropriating, recuperating, and adapting (Cué, 2014),” especially in the intimate and often solitary stages of ideation and prototyping.

Radicalized

In an experimental attempt to bring user participation to a new level, an eminent design firm in New York City decides to broadcast their entire design process online for one week. At any point during this period, viewers are able to leave comments directly on the work in progress, wherever the design stands in the moment. As an additional constraint, firm directors insist that production designers incorporate suggestions from viewer commentary into the work. While these restraints create a chaotic and maddening environment for the designers, the experiment yields some interesting results and inspires the firm to propose a more manageable and formalized version of the experiment... (fig. 3)

Normalized

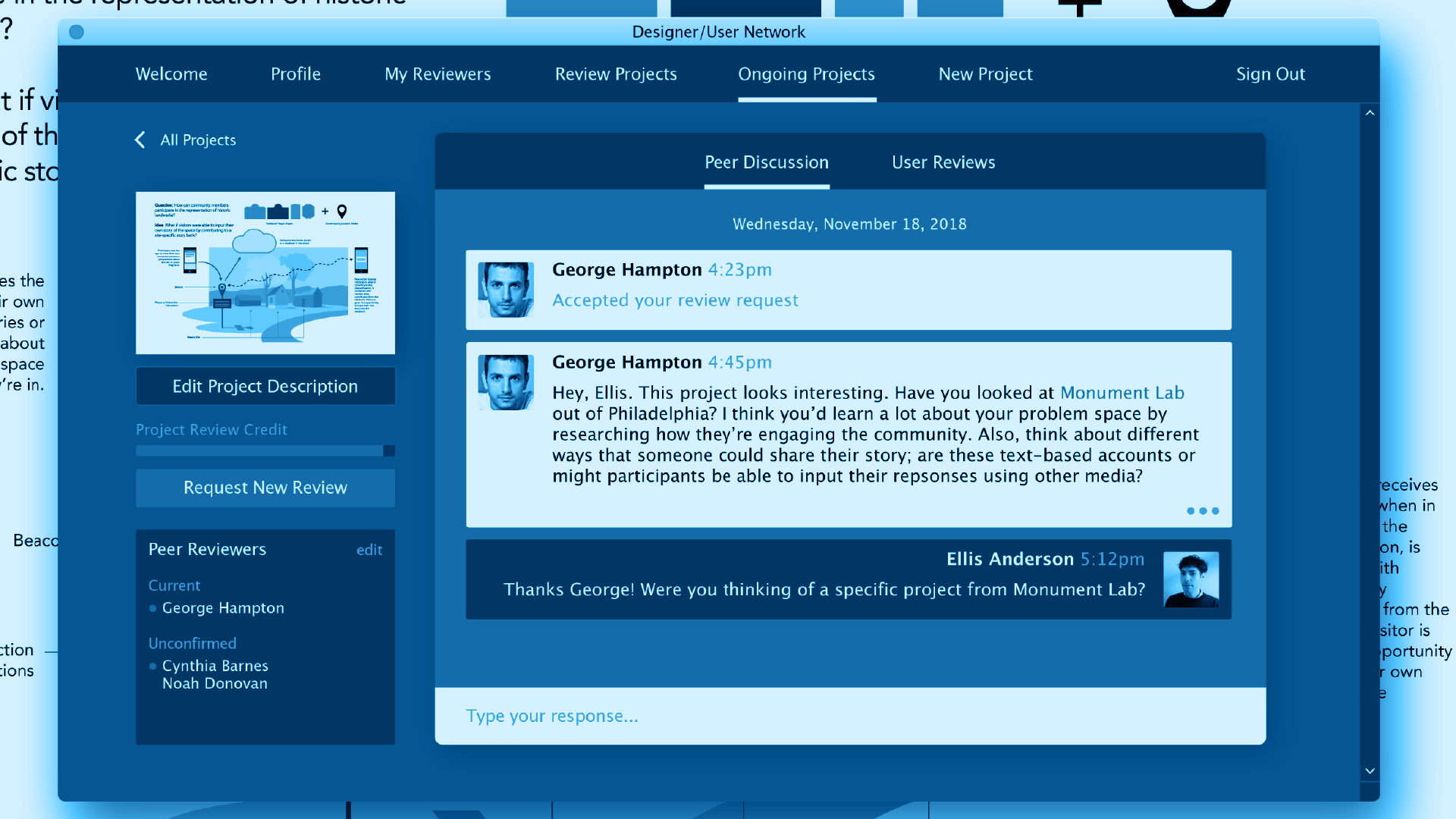

Adobe introduces the Designer/User Network (DUN), a plugin for their application suite that connects individual designers with peer designers in their field to review and critique unfinished or ongoing projects. By exposing a project to peer review in the interim stages of ideation, DUN encourages the designer to free up private and potentially restricting behaviors when synthesizing project briefs, defining the problem space and beginning the ideation phase on their own. The system allows fellow designers to provide pertinent suggestions or perspectives on the work in the intimate stages of ideation, expanding the potential for ideas in the prenatal stage of a design. Designers receive credit for reviewing other designers’ projects and giving valuable feedback. The project initiator determines the value of peer feedback by voting on its usefulness and pertinence to the project. Reviewer credit is then used to “pay” for feedback on their own work. In addition to the peer review system, DUN introduces a way for designers to receive user feedback on work in progress. By offering coupon rewards to potential users, Adobe’s User Review Forum (URF) publicly displays designers’ ongoing work and prompts users to input their responses based off criteria specified by the project type and project designer. By opening these designs to user review, designers are able to receive a preliminary user assessment of project direction, quality and relevance, before or even in place of official user testing.

References

- Cué, P. (2014). On the wall: Designers as agents for change in environmental communication. Visible Language, 48(2), 70-83.

- Gonzales-Crisp, D. (2017). Syllabus. Grad Studio GD502: Design as a Cultural Artifact.

- Greenhouse, E. S. (2012). Human-centered design. Retrieved from Livable New York: http://www.aging.ny.gov/LivableNY/ResourceManual/DemographicAndSocialTrends I, 9.